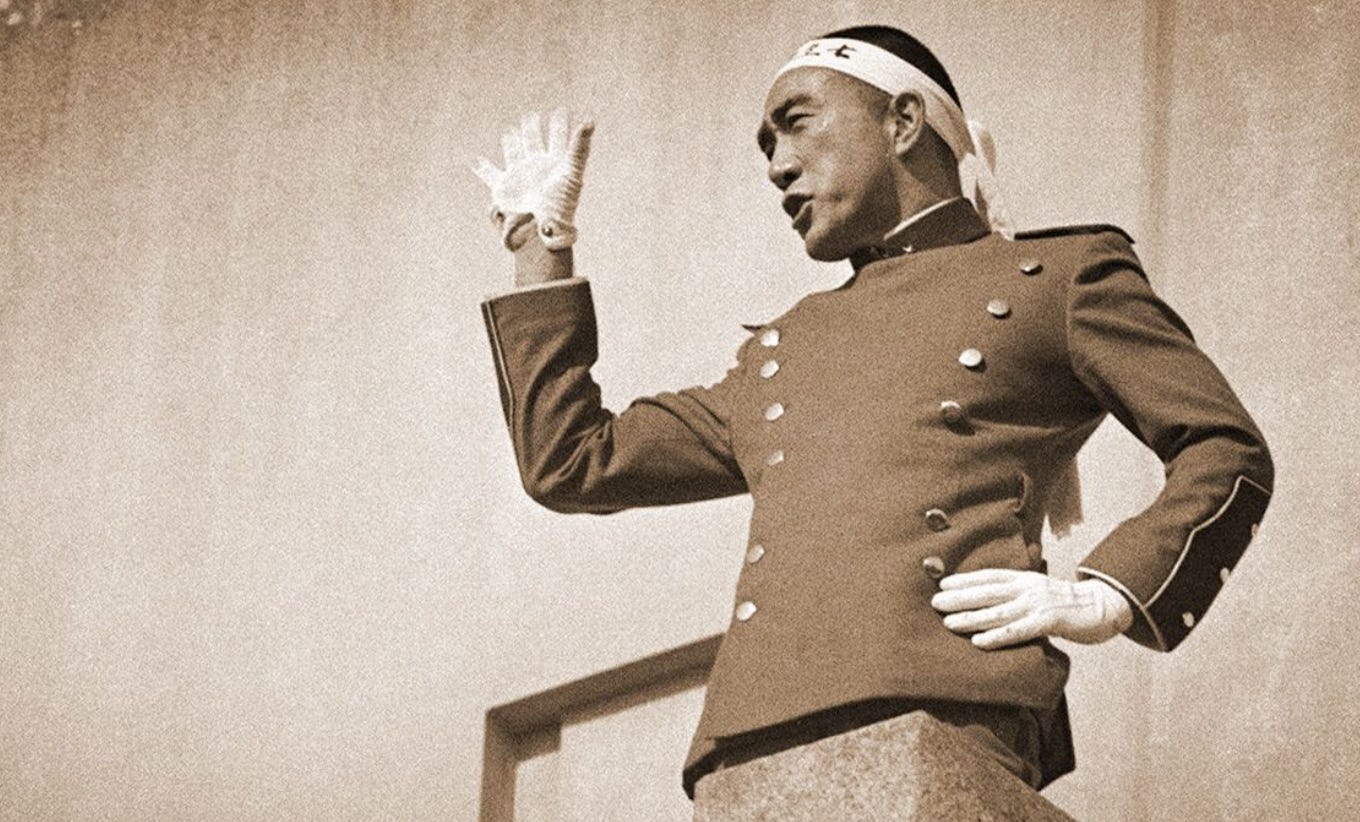

I finally read Osamu Dazai’s (left) No Longer Human, a novel I had known about for years but somehow avoided. Dazai’s story of Yozo, the perpetual “clown,” still haunts Japanese youth who feel alienated from their families, workplaces, and nation. My own connection to Yukio Mishima (right) is more mischievous: in 2017, I released a farewell idol track called “Seppuku” that samples his voice and is pretty troll-ish.

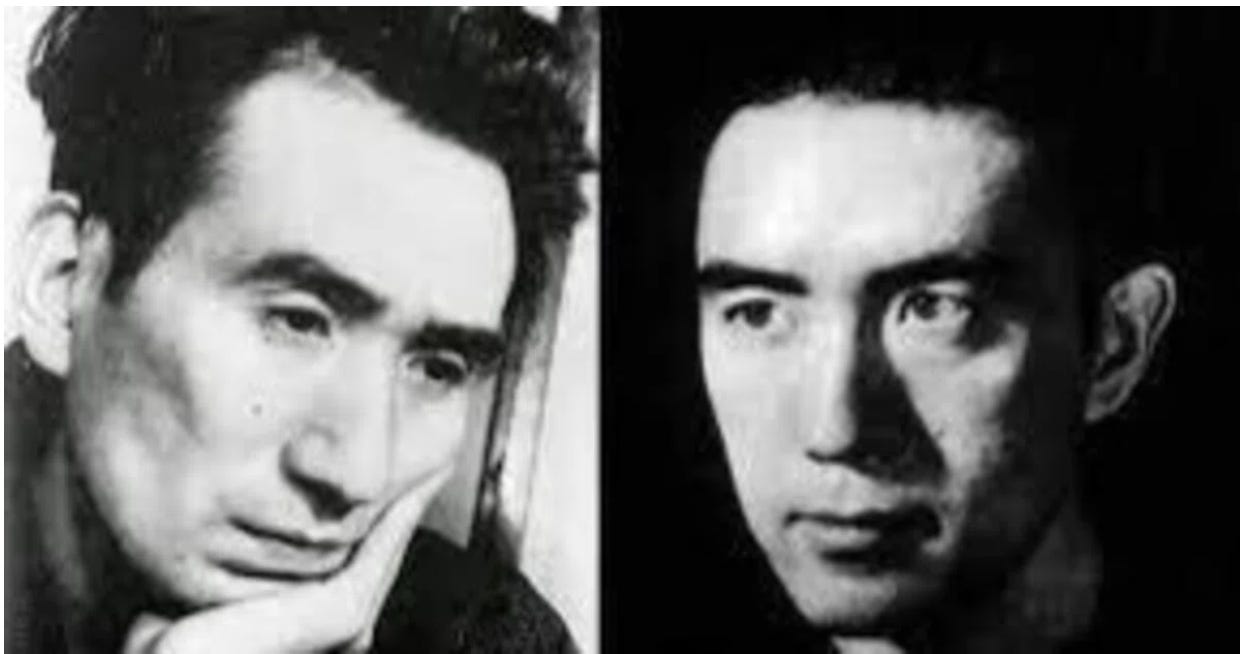

(Album art of me committing Seppuku with candies coming out of my stomach by Japanese guro-artist Shintaro Kago)

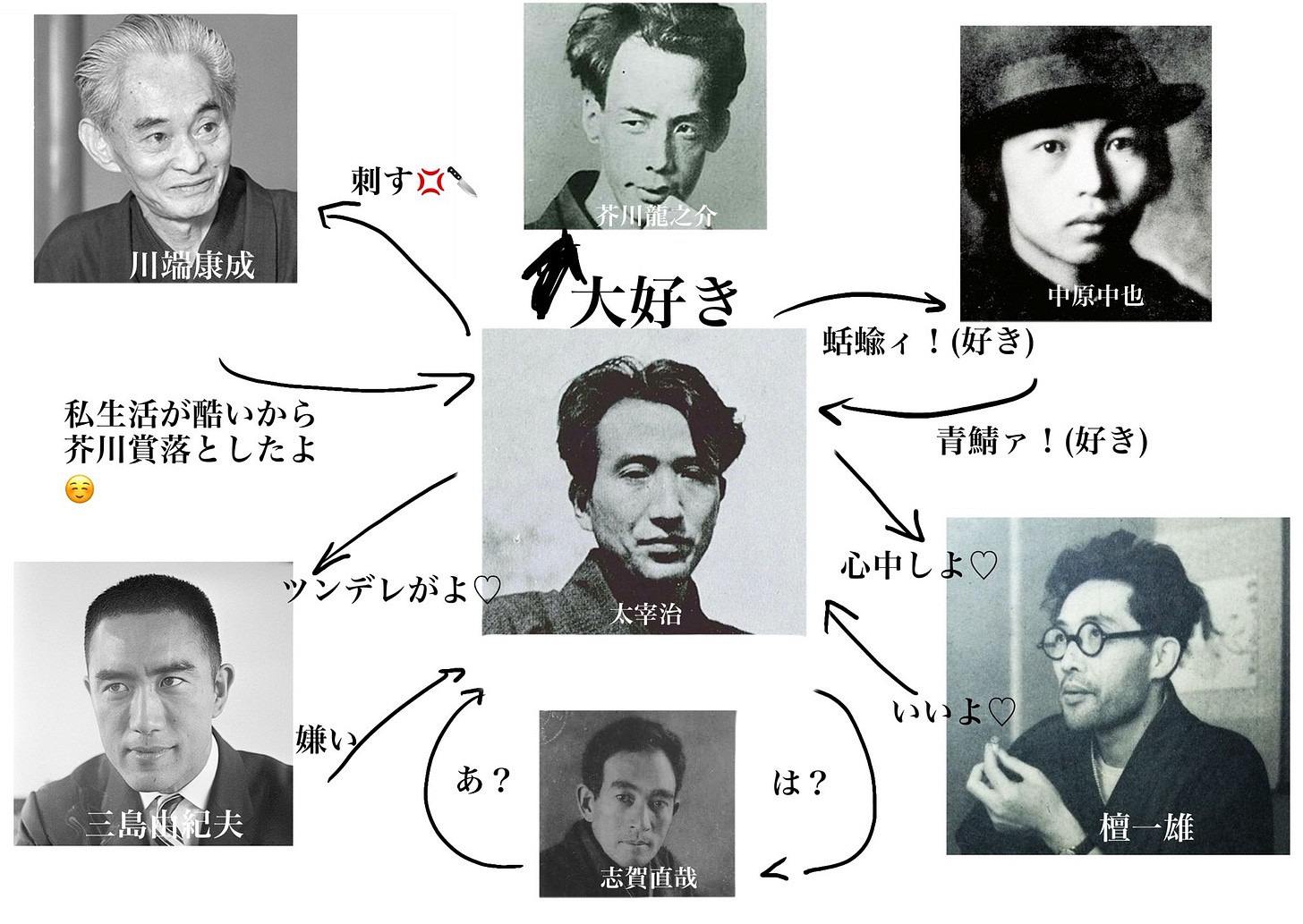

Both men were more alike than not. They came from privileged families, caught fire in the immediate post-war literary scene, and died by their own hand, Dazai by lover’s suicide in 1948, Mishima by ritual seppuku in 1970, yet their temperaments and politics could not be further apart. However, we can examine their literature, lives, and reactions to a difficult post-war period as precursors to some of the cultural issues facing Japanese youth today.

Dazai vs. Mishima

Osamu Dazai (1909-1948) wrote in a confessional key, and I have to admit it’s pretty annoying at times. Apparently, this style of writing is called an I-novel, which is a somewhat fictionalized memoir that was quite popular at the time. His tone, however, is almost drunk on its own despair. Critics have called his style whiny both then and now. He’s been compared to JD Salinger by many Western literary critics. This comparison is usually due to the sophomoric tone of both of their most well-known protagonists, although, less discussed is the childhood sexual abuse he hinted at in No Longer Human, which is interestingly another comparison to Salinger’s Holden Caulfield in Catcher In The Rye. I understand the appeal of such stories and what they offer young people in societies that rarely discuss feelings, but I can see why Mishima would find this annoying.

In post-war Japan, Dazai’s wounded voice struck a nerve with readers who felt equally dislocated. He was quite the troubled man and has a colorful Wikipedia page. Throughout his life, Osamu Dazai has made multiple failed suicide attempts, including two separate double suicide attempts with various women, before “succeeding” with Tomie Yamazaki. No Longer Human’s draft was completed mere days before this event.

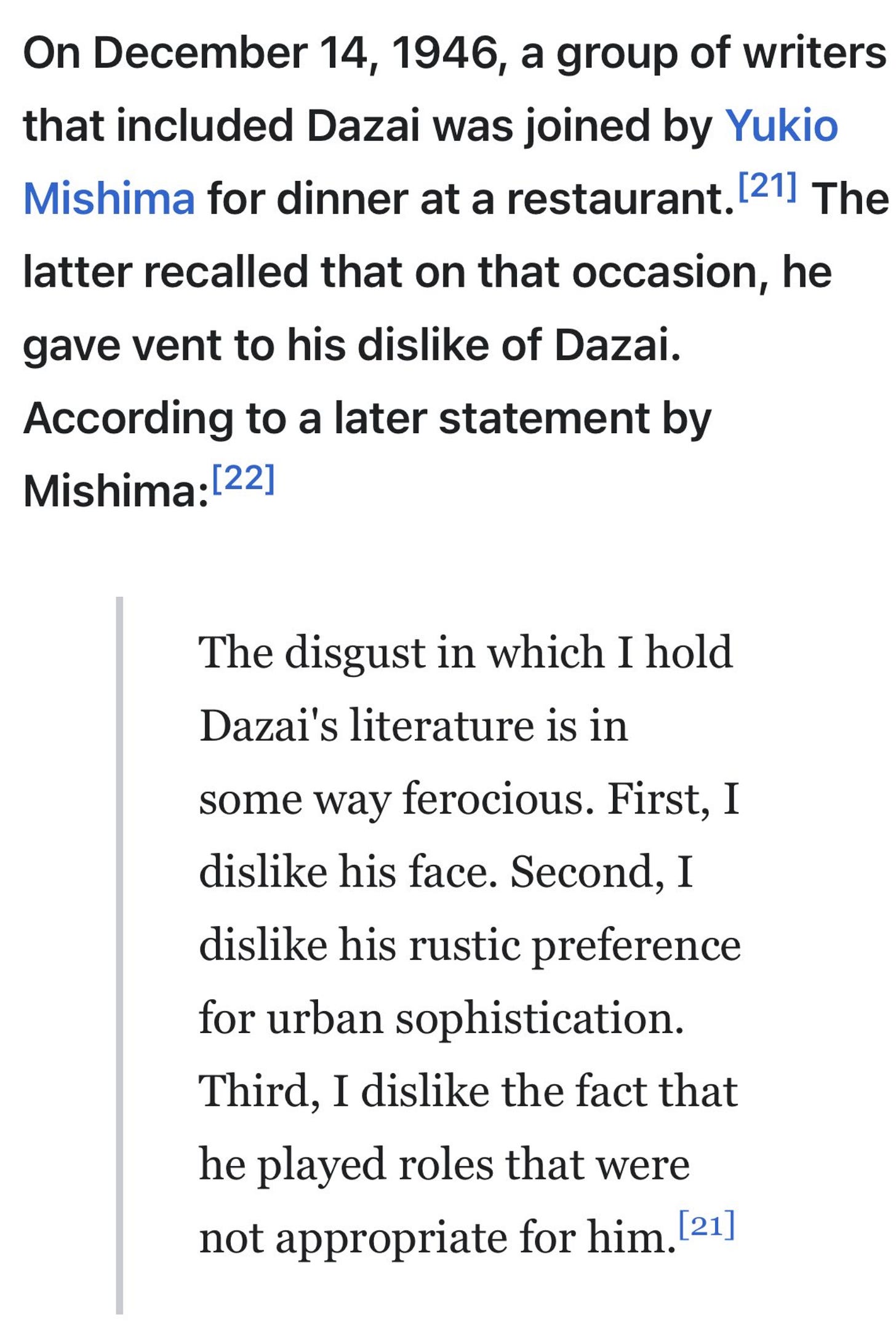

Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) recoiled from Dazai’s decadence. At a 1947 literary dinner, he complained that Dazai “clowned around and wasted everyone’s time,” later writing essays that blasted the “school of self-indulgence.”

In fact, Mishima wasn’t the only person who took issue with Dazai’s style at the time. He was quite controversial among his contemporaries.

(A relationship map outlining the relationships Dazai had with his contemporaries, in the style of teen girl magazines. Posted by this X user. I’m not very familiar with all of these literary figures, so I won’t expand on them, but I found it hilarious.

Mishima cultivated an opposing persona to the meek, perhaps even exposed and vulnerable, style of Dazai. He was a (semi-closeted) homosexual bodybuilder who was obsessed with the male physique and an evangelist for emperor-centric nationalism. And just like Dazai, some of his stories foreshadowed his own real-life death; his books, "Patriotism" and The Sea of Fertility, feature characters who die by seppuku. It’s no stretch to see Mishima and his fatalistic romanticism of yore as a forefather of Japan’s modern right wing and even a touchstone for some Western reactionaries.

The feud remains relevant because it reflects the choices facing Japanese men today. Sanseito, the Japan First political party, is rapidly gaining power, and behind them is a leader who insists on re-establishing imperial rule. Mishima’s outward-projected aggressiveness, echoed in online nationalism and the cult of stoic self-improvement.

On the other side is Dazai’s inward-looking despair, which resurfaces in contemporary hikikomori and even the phenomenon of “herbivore” men.

Both of these reflexive impulses arise when traditional scripts of duty collapse and economic confidence fades. These are men, from a traditionally masculine society, who have been emasculated by a defeat on the global stage and post-post-modernism. As we look at the state of the industrialized world and the morale of men, maybe Japan itself a peer into the future of post-post-modernism

Japan’s task is to forge a masculinity that neither wallows in Dazai-style fatalism nor reenacts Mishima’s balcony theatrics. A healthier model would own historical failures, cultivate civic courage, and marry technological creativity with emotional literacy.

Supplementary content: This is all in Japanese, but it features a scene depicting the notorious confrontation between Dazai and Yukio Mishima. It’s from a film about Dazai’s affairs as a womanizer.

"even a touchstone for some Western reactionaries."

i move in reactionary circles. many of them love him. read his translated works like they're scripture. (i've never read)

Japanese culture is intensively introspective which makes it hard to calibrate to the outside world. It yo-yos from intense pride (Mishima and pre WW2 genyosha peaks) to emasculation.

The more interesting time was the immediate postwar period where Japan quickly integrated with the outside world and had self-confidence without the deadly arrogance.

After the bubble crash, Japan has just been stagnant and they’re trying to figure out their identity in a world that’s starting to leave them behind. Depending on how they integrate would determine the face of masculinity moving forward