A little over a decade ago, I left my small town in suburban Michigan and performed as an idol in Japan. Considering it was quite a while ago and not something I am involved with much these days, I don’t want to be stuck in the past by mentioning it. But it does come up a fair amount of time, so I figure I can point people here when it does…

We’ve all met the guy who would’ve gone pro if he didn’t pull his ACL in 1992, or the former “gifted kid” who is now an adult who still feels the need to mention their SAT score. Nobody wants to be that guy. That guy doesn’t want to be that guy.

Being proud of your accomplishments and bragging about them is good. Being fixated on them, with a juvenile preoccupation with the past, isn’t.

With that said, allow me to talk about my past a bit…

TLDR;

I live in San Francisco and have worked in technology full-time for 5 years. 10 years ago, when I was 18, I left my small town in Michigan to perform as an idol in Akihabara and then later the wider Tokyo area.

OK, here’s the meat & potatoes of everything (i am a midwesterner so it, naturally, will come to meat and potatoes~) In 7th grade, I moved from a middle-class neighborhood in Detroit to a working-class White suburb and immediately committed social suicide. During lunch, some kids were talking about WWE, and I, with all the confidence of a kid who’d just discovered critical thinking, announced that professional wrestling was “~~fake and gay~~”

To my horror, I was ostracized immediately.

Looking back, I realize those kids understood something I didn’t: the point of show business is to put on a good show. The performance is the product. The kayfabe is the point.

This same principle would define my entire career as an idol in Japan, though I wouldn’t understand it until much later.

I wasn’t a weeaboo in the traditional sense. I was a weird kid with an insatiable appetite for information about other cultures. I’d check out books on Greek and Egyptian history from the library. I’d hit up the small Telugu-owned corner store to get bootleg Bollywood films. Japanese pop culture was just one interest among many, and my parents(bless them) thought I’d become an anthropologist.

I grew up in suburban Michigan during the death throes of the auto industry. At one point, the majority of Japanese speakers I knew were Gen X White and Black American women who’d learned the language at the industry’s peak. My public high school offered Japanese classes. I began taking private Japanese lessons when I was 11 years old.

Here’s the thing about non-native instruction: I could read and parse grammar, but I couldn’t really speak. And what’s the point of learning a language if you can’t communicate?

So at 15, I started livestreaming on Nico Nico Douga, a proto-Twitch platform for Japanese otaku subcultures and gaming. I was an absolute oddity. A Black American teenager singing and making corny jokes in broken Japanese, trying to practice in real-time in front of thousands of viewers.

In addition to livestreaming, I also initially went viral as a maid at a very short lived brick & mortar maid/anime cafe in Detroit’s hipster district when I was in high school. The cafe was covered on local news but was then shown on a Japanese variety show. This got me a lot of attention from the Japanese public and started an initial wave of people following me on Twitter, my blog etc.

(here’s fan art a man from Hokkaido created and sent me, roughly 13 years ago!)

I was never super mega ultra famous, but I got noticeable attention from these livestreams. When I later moved to Japan, people would stop me on the street in places like Harajuku would occasionally stop me and say they watched me on Nico Nico Douga!

At the time I got popular on NicoNico Douga, a character was released in an idol rhythm game with a suspiciously similar background! Her name is Jedah and she's a 17-year-old Black American girl interested in Japanese culture, with a birthday a few days from mine.

I can’t prove it’s based on me, but come on.World Otaku Mate, the NicoNico Douga channel I worked with, was affiliated with a indie music magazine. They saw the traction I got from my livestreams and began experimenting with talent management. I was offered representation as an idol in Japan.

At the time, I was still in high school, also performing at chiptune shows in Ann Arbor. I had no idea what I was doing.

I know that is the part that sounds like luck, but it wasn’t really. I’d been creating public, searchable content in Japanese for months. I’d built an audience. I’d demonstrated I could perform and connect with Japanese viewers. When someone was looking for talent that could bridge Japanese and Western audiences, I was findable.

So…January 1, 2015, I moved to Tokyo and started performing solo in Akihabara. For the first eight months, I was completely directionless. I had a few big TV appearances, some modeling gigs, but mostly floundering. My first manager quit the agency I was signed to. I was about to leave entirely.

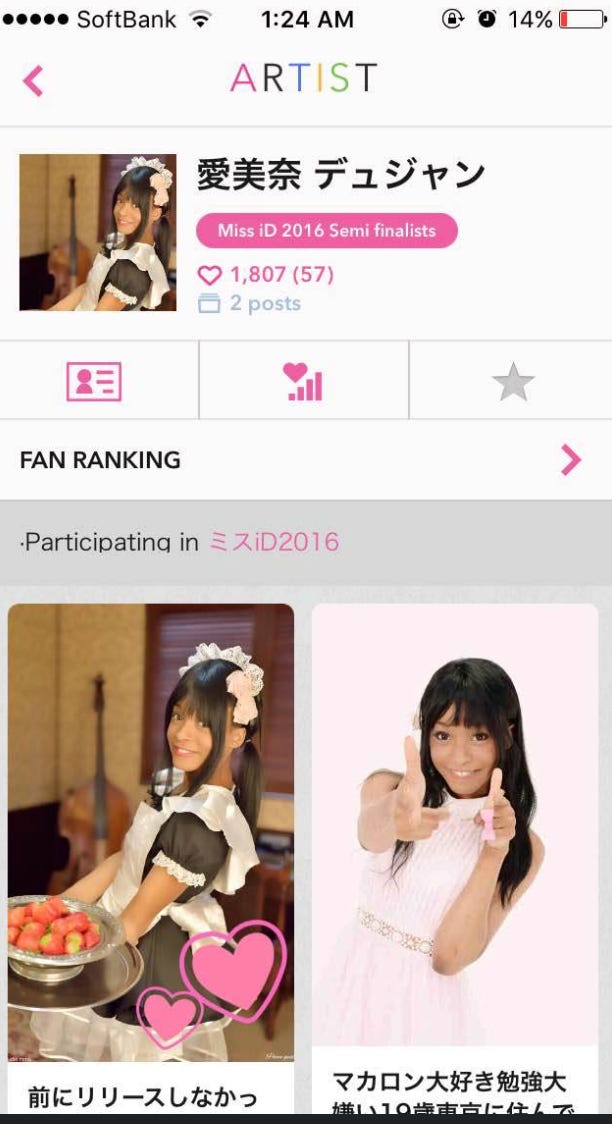

Then I entered Miss iD, Kodansha’s idol competition, which I’ve always described as “if VICE magazine made an idol competition.”

Miss iD was experimental even by Japanese standards. It was essentially an accelerator for “idols and strange women with mainstream appeal potential.” The pitch was “for women who haven’t been given a chance by the rest of society,” though many competitors were exceptionally talented or attractive. They just had some odd trait that made them unmarketable by traditional standards.

I won a spot. I didn’t win the grand prix award as I would have liked, but I won a runner-up award in a contest that thousands of women competed in. The woman who won the Grand Prix award my year, Moeka Hoshi, has gone on to win an an Emmy for her work in the show Shogun!

At the time, this changed everything. Suddenly, I had structure, a team, visibility through a major publishing company, and a cohort of other weird, ambitious women navigating the same industry.

Later, I joined Chic Girls, described as an “Ariana Grande-inspired sexy/cute dance group,” where I performed 2-3 gigs per day while attending university full-time. I’d have dance class in Harajuku, a compulsory team lunch, then dash by cab to Nishi-Azabu for classes. It destroyed my immune system but established my career.

What Being an Idol Means

Before going further, let me clarify what an idol is, because Korean idols have warped most Western perceptions.

Japanese idols aren’t polished products. They’re young performers. Idols are singers, models, and actors, known for their personalities. Fans follow them to watch their journey, not to see perfection. Think American Idol contestants or influencers before influencers existed. The appeal isn’t a finished product; it’s watching someone try really hard to improve each performance.

The industry exploded in the 1980s “golden age” with commercial tie-ins to anime and products. The idol was a commodity selling a commodity. By the 2000s, the internet disrupted everything. Women like Momoi Halko started self-producing with personal blogs and recording equipment. When I started in the early 2010s, there were tens of thousands of active idol groups in Japan, many started by small companies to promote products.

(this is a screenshot from my profile on the Showroom app we were promoting in the contest)

Much of my work was promoting fashion or technology products. In Miss iD, we were essentially meant to promote SHOWROOM, a chat app similar to Twitch where idols interact with fans. I also participated in a gameshow to promote the newly released Line LIVE streaming feature(LINE is basically like WhatsApp for Asia).

The industry is supported primarily by adult male fans who either live vicariously through idols or have pseudo-relationships with them. These fans are typically harmless, though there have been aggressive incidents.

(modelling for jenny fax / mikiosakabe in Tokyo Fashion Week)

The Rules (AKA The Kayfabe)

Remember that WWE lesson from 7th grade? The Japanese idol industry is largely kayfabe that fans happily pay for.

Western idol fans, like my 7th-grade classmates, get quite angry when I say this, but most “rules” are performative. They’re about maintaining the illusion for paying customers. Here are the actual rules I encountered:

The “Love Ban Law” Idols supposedly can’t date. This maintains an air of availability for adult male fans buying photos and handshake tickets.

In reality? After management companies tried suing women for falling in love (viewing it as depreciating their investment in training), a Tokyo court ruled they legally cannot restrict dating in contracts. Now they work around it by claiming they “control your image.”

Which somehow feels worse.

No Photos With Men: Even if a random guy asks for a selfie or your cousin visits, you can’t take photos with men. Someone could post it online, start rumors, and alienate fans, which stops cash flow.

No DMs on Social Media: Here’s what Western fans don’t know: many idol fans aren’t shy 30-year-old salarymen. They’re antisocial guys in their early-to-mid twenties who try to date the idols.

Fans will message girls, form bonds, lavish them with gifts, then screenshot everything and post it online to defame them when things go south. To avoid this, management doesn’t allow DMs with fans and may even ask for your social media passwords.

No Tweeting Between 11 PM - 8 AM: Yes, this is real. After leaving my first company, another agency told me this would be required. They said a woman’s reputation could be tarnished if she were seen as “the type of lady who tweets at midnight.”

Lulz.

No Drinking/Smoking: Standard image control, even if you’re of legal age. They also told us this was to keep us in good health, which is probably true tbh.

No Working in the Adult Industry “Adult work” girls’ bars, hostess clubs is ubiquitous in Tokyo, especially among the type of girls interested in idol groups (subculture kids, wayward women). Most companies have a blanket ban.

This varies by group. By the time I was in Chic Girls, management basically said “don’t be reckless” meaning don’t send nudes with your face in them or go on IG live with a guy in the background. Many members worked at high-end hostess bars. Nobody cared.

Hardest Parts

Workload Attending university full-time while performing 2-3 gigs per day destroyed me. Some days: dance class all morning in Harajuku, compulsory lunch, then sprinting to catch a cab to Nishi-Azabu for university. My immune system collapsed. I trained myself to be busy every waking moment.

When I moved to England later, I had no idea what to do with my free time.

Bullying: This wasn’t an idol thing or a Japanese thing; it is a “social group of young people” thing. When I joined a group, I got bullied. This didn’t happen performing solo in Akihabara… those girls were curious and kind. Thankfully, one of the group members spoke up about the bullying, and the perpetrator was ousted.

Most idols, even famous ones, are genuinely kind people. But group dynamics are group dynamics everywhere.

The Best Parts

A few years ago, I went through my Facebook message requests. My inbox was filled with Japanese women sending words of support and love.

I remember riding my bike around Jujo, the small provincial part of Tokyo where I initially lived. Occasionally, school children or elderly people who’d seen me on TV would yell “Ganbatte Aminyan!”

In my youth, I pursued fame because I wanted to know I was loved. I realize now this was probably not the best way to acquire love. I’ve done a lot of work since then and grown considerably.

The idol industry is deeply tied to technology and the Japanese economy. The 1980s golden age produced countless acts with commercial tie-ins. The 2000s internet era enabled self-production. By the 2010s, social media meant tens of thousands of groups could exist simultaneously.

I entered at the perfect moment: when being a bilingual, internet-native performer with an American audience was actually valuable to Japanese companies trying to expand internationally.

The kayfabe was always the point. The rules, the availability, the “no dating” myth, it’s all performance. Fans know this on some level. They’re paying for the illusion, the parasocial relationship, the feeling of supporting someone on their journey.

I learned Japanese through unglamorous years of flashcards and grammar drills. I practiced by humiliating myself in front of thousands of strangers online. I got discovered by being discoverable, creating consistent, public content that demonstrated my abilities. I succeeded by entering competitions, joining groups, and working myself into exhaustion.

None of it was all that romantic. All of it was real work wrapped in layers of performance.

Thanks for reading!

This certainly wasn’t everything, and I’ve debated with myself about how much I actually want to discuss this. My life has largely moved on from this but I think I may occasionally write more thoughts on it. Bye for now.

I never thought I would see a mention of Miss iD on Substack of all places. I was deep in the world of Japanese idol reporting and fandom 10 years ago and remember seeing your stage name on social media and platforms like Showroom from time to time. The rules and not easy life you describe were well-known to me at the time, but it's heartwarming to hear about the best parts that you experienced.

Hey what a story! If you would be interested on a cross-post writing, we’d love to have something about your time as an international student in Japan and juggling being an idol. It would be for CollegeTowns.org. Thanks.