In late November 2024, Dr. Ally Louks went viral for her dissertation, “Olfactory Ethics: The Politics of Smell in Modern and Contemporary Prose.” Her sudden fame resonated with many people’s frustration about what they see as decadence in non-STEM fields. In 2020, when I completed my undergraduate dissertation, I considered pursuing a PhD in cultural anthropology. My hesitation then, like the backlash Louks faces now, came from the sense that some academic work appears navel-gazing, juvenile, and narcissistic. In an era where universities have replaced churches as arbiters of truth, many are tired of what feels like decades of finger-wagging by scholars who seem disconnected from reality.

Some observers claim this criticism is misogyny. The “softer” social sciences and humanities, where women predominate, tend to receive less respect. Perhaps there is a tinge of truth in that, and I have thoughts about politicization and replication crises in these fields that I will save for another post.

Still, the backlash cannot be attributed solely to sexism. Whenever NASA* spends a fortune to smash an asteroid just cuz, people shout, “That money should have fed hungry kids instead.”

*spent? Does NASA even exist anymore? lulz

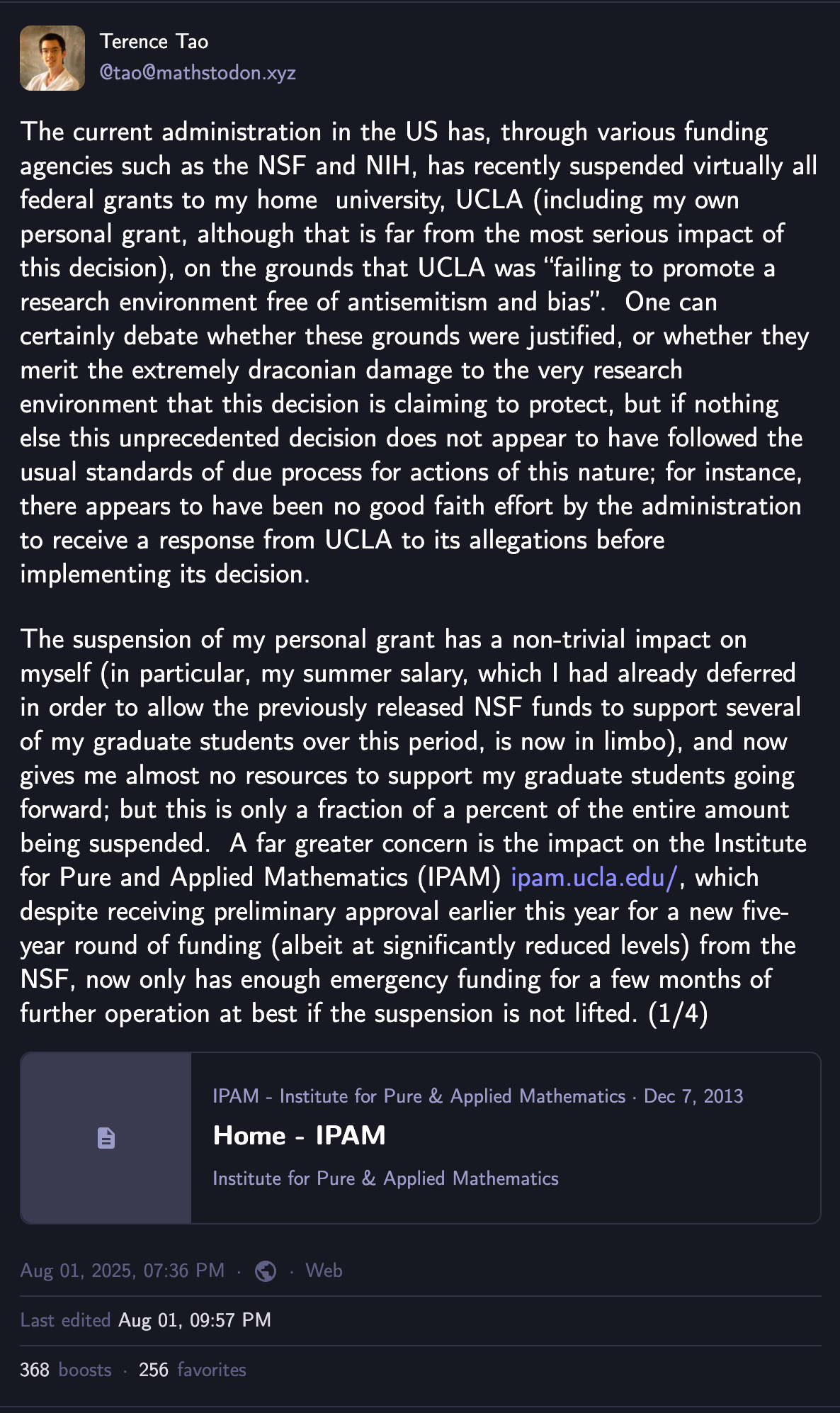

As of last week, Fields Medalist Terence Tao posts that the U.S. government has suspended virtually every NSF and NIH grant at UCLA, including his own pure-math funding, over claims the campus “failed to promote a research environment free of antisemitism and bias.” This funding pull was primarily due to UCLA allowing pro-Palestine protesters, but the sentiment that many have in response to this is the same: information and the pursuit of it based on sheer curiosity is not worthy enough, on its own, to triumph over other values that we hold.

To the vast majority, the only “worthy incentives " for pursuing information are curing an awful disease we are afraid may kill us(or our loved ones) or making lots of $$$.

Smell studies and mathematics could not be more different from one another, yet both incidents poked the same raw nerve: people are tired of what feels like decades of finger-wagging and bottomless funding for work that seems disconnected from ordinary life and is unclear about its purpose.

There is a general distrust of research for its own sake and information for the sake of merely gathering and synthesizing knowledge.

In this post, I’ll explore:

What is the value of information for information’s sake?

When does this become diminishing returns?

What are some long-term use cases for having a ton of information archived?

How much is too much?

When I say “information for information’s sake,” I mean knowledge gathered with no immediate promise of profit or lifesaving utility. Pure curiosity, in other words. Some worry that we humans lack the storage capacity for endless data, yet modern cloud infrastructure can warehouse exabytes at trivial cost. So what is really too much?

Perhaps, the real bottleneck is cognitive, not physical. Claude Shannon demonstrated that adding bits increases entropy, but it does not necessarily mean that. Empirical work bears this out: a 2023 meta-review of 180 information-overload studies reported that comprehension and decision accuracy fall twenty to forty percent once data volume crosses a cognitive saturation threshold, and a 2024 study in Information & Management found that dashboard-flooded employees grew less trustful of expert advice, defaulting to gut heuristics instead.

Cultural “overfitting”?

I recently remembered intricate Black-American hand-clap games from my girlhood. As American schools have become more ethnically integrated and children spend less time with off-screen play, many of the rhymes and hand games are being forgotten over time. Surely someone has a dissertation on that, I thought. Half flippantly but also wondering, does it matter if this tradition is lost in time or saved for some purpose we can’t really conceive of yet?

Cataloguing every custom is noble until we drown future scholars in trivia. Entire civilizations flourished for millennia, yet we don’t even know what they called themselves because their records vanished. Would rediscovering every lost inscription change modern life? Perhaps, or perhaps it would sit in a digital attic that no one opens.

What are such diminishing returns of funding, producing, and investing in wide-scale information gathering efforts that may have little to no impact on life? Will these factoids just be more noise to academics who could use their intellect on worthier causes?

Information ≠ insight

History has also shown that when technology increases information transmission, it often comes with social upheaval due to the new information that it facilitates.

See: the Protestant Reformation/Enlightenment’s printing press, radios, and the early 20th century, the modern internet, and global social destabilization.

It is possible that the production of more information leads to less overall cohesion. Some researchers have dubbed our current period as one of "cyber balkanization”. Although mass media was somewhat an anomaly that didn’t exist prior to the 19th/20th century, neither did nation-states in their current forms. A society without mass media, a shared culture, and a clear vision in an environment with an endless amount of information may pose trouble for maintaining such nation-states' peace.

Potential Value of “make-work” scholarship

This isn’t directly related to the information itself, but rather to the potential social benefits of funding such research. Even if the information itself may never have much of an “impact”, pragmatically, shepherding academics off into corners where they can play may be a good thing.

Doctoral study acts as a social capacitor, keeping restless minds occupied, building cultural capital, and preventing an overeducated yet underemployed class from festering into backlash politics. Many brilliant people are simply not suited for corporate life.

Also, in applied fields such as Human-Computer Interaction, industry doesn’t have the luxury of chasing every weird idea; academics do. Xerox PARC and Stanford Research Institute midwifed the mouse, the GUI, and early NLP. Tao’s own Institute for Pure & Applied Mathematics (IPAM) runs summer programs whose alumni now lead teams at Google, NVIDIA, and NASA.

Takeaway

Too little information starves culture; too much drowns it. A true measure of a society’s prosperity may be the ability to study underwater basket weaving to one’s heart’s content.

i think to some extent we can evaluate a field independent of is immediate utility. a society, a human culture, that is wealthy but does not fund or cultivate any advanced mathematics seems to me to be missing something. this isn't universal; the greeks thought pure mathematics was a deep metaphysical enterprise, while it had a much lower status in china.

but what about various cultural studies which are very new? i think unlike mathematics or history or philosophy these disciplines haven't really proven themselves as edifying nor are their methodologies really validated.

i guess i would just say it depends on the field, and we know domains worthy of knowing when we see them (speaking as someone who has been asked my whole like "why would anyone want to know that!")

I'm in the odd position of disliking Ally Louks because of her shallow online presence, but seeing her research as basically valid, and probably better than most humanities dissertations, which are so full of postmodernistic garbage as to be incomprehensible. The backlash against her actually reveals why many rely on postmodernism: a lot of people, when shown gibberish, assume they aren't smart enough to understand it. Her thesis is not gibberish so people feel entitled to criticize it. But it would be better to criticize the gibberish.

In terms of the overall point, I think far too many people are getting degree at every level. Colleges need to roll back grade inflation and become a lot more selective.